The Transforming Heart of Christianity

III - The Nature of God and Holiness

The Rev. C. Joshua Villines

Virginia-Highland Church

March 19, 2003

As Christians, we worship God as revealed in the Christian scriptures. This might seem like it should be obvious – but in our pluralistic culture it is not. Sometimes in our effort to be inclusive or sophisticated, we attempt to blend our religious beliefs with those of other faiths in an attempt to claim that we all really believe the same thing.

We do not. Christians have a unique understanding of the nature of God. We can learn from other faiths. We can even find common ground with other faiths; but there are very clear boundaries on who Christians have understood God to be.

The foundation of that understanding is found in two passages from the Hebrew Bible. In Deuteronomy 6 there is the “Shema” – so named because that is the first word of the passage in Hebrew. “Hear, O Israel, the Lord our God is one. You shall love the Lord your God with all your heart, and with all your soul, and with all you strength.” [Deut 6:4-5]. For Christians, as with Jews and Muslims, there is only one God. We are monotheists. There are very few absolutes in our faith, but that is one of them – and all Christian theology is predicated on that understanding.

We use Lord there in many English translations because the passage includes the name of God which is sometimes written in English YHWH for the Hebrew letters hwhy. We say “ Lord” because no pious believer at the time it was written would have ever dreamt of actually pronouncing that name. Instead, when reading aloud, they might have said simply “Ha Shem” (“The Name”) or “Adonai” (“Lord”).

This is another absolute in our understanding of the nature of God. Not only is God one and singular, God is holy. Holy literally means “set apart,” different. When God reveals the holy name which should not be spoken [Exodus 3:13-15] God says simply, “I am who I am.” That’s really as far as we can get in understanding the nature of God.

God is not created in our image. God is not like us. God does not die. God is not limited in time or space. God does not see the world or us the way we do. God does not value the things that we value. God is holy.

God is holy and God is one. Everything else that we talk about in terms of Christian theology rests on these two principles. There’s only a small problem with that, one that Jews and Muslims do not face. What about Jesus and the Holy Spirit?

The divinity of Jesus is unquestionable in the biblical record [MT 9:6, 25:31; Philippians 2:6; Heb 1:2-3]. Likewise, the Holy Spirit is clearly also God [ John 16:7-13]. So do we as Christians have three Gods, or only one? Returning back to the beginning, to believe in even the most basic message of the Bible we must believe that there is only one God.

How do we do that and also believe the biblical record about who Jesus is and who the Holy Spirit is? Enter the doctrine of the “Trinity.” At this point, I must interject the disclaimer that if we think we understand the doctrine of the trinity we are doing it a disservice. The Trinity is, by definition, an implicit contradiction. We believe that God is one and that God is three.

God, Jesus, and the Holy Spirit. This is attested specifically in two passages in Scripture [I John 5:24; II Cor 13:13], and implicitly in dozens more where we read of Jesus’ divinity and the nature of the Holy Spirit. The two explicitly Trinitarian passages are probably later additions to the scriptures which contain them; but they are very old additions. From very early on in it’s history, the Church has believed that our singular God is also three distinct persons.

If defining God were a science experiment, that hypothesis would fail. But God is not subject to the scientific method. God is holy, separate, other. God is not bound by our logic or our understanding of the world.

It is important, then, to try not to rationalize this with easy explanations. I have some notes from a class which I took with Jim Denison in which he lists some of the errors we can make in trying to understand the nature of the Trinity. Rather than reinvent the wheel I’ll simply list the ones he names:

The Trinity is like water. It is one substance with three different forms (ice, water, and vapor). This is the fallacy of modalism. God, Jesus, and the Holy Spirit are in fact separate and one. Not three forms of one thing.

- God is like a corporate partnership. This fails to acknowledge God’s unity.

- God is like a three-sided pyramid. Each side is separate but the sides function together. This ignores the fact that the roles within the Trinity are not static. The three parts of the Godhead are dynamic.

- Even my favorite image of perichoresis – three people dancing together in a circle, fails. I still like the image of three separate persons moving constantly and rhythmically as one; but it also undermines the concept of the Trinity being one; not just appearing to be one.

There is no analogy that will work, because the Trinity is, by definition, incomprehensible to us. God is holy and mystery, and as Christians we accept that the nature of God is beyond our comprehension. We cannot allow ourselves to fall into the trap of cramming Christianity into something we can fully understand. Doing so unduly elevates ourselves and debases God.

At the very least, however, we can define our limited experience of how we can relate to the three persons of the Trinity. To begin at the beginning, we experience God (or “God the Father” or “God the Mother” or however we wish to relate to that part of the Trinity which is not Jesus or the Holy Spirit) as Creator [Genesis 1]. In the beginning, there was nothing except God, and God created the world and us in it.

How does God interact with that creation, and specifically with us? Through love and covenant. Everything that we experience of God is rooted in God’s love for us and God’s desire to be connected to us. John 3:16 – “For God so loved the world that He gave His only begotten Son that whosoever believeth in Him should have everlasting life.” That verse is much overused, but with reason – it describes the heart of our faith.

We are so loved by God that God made a huge sacrifice to be able to be in a relationship with us. This is essential to our continuing theme of how Christianity transforms us. Being loved by someone always changes us. We know, without a shadow of a doubt, that the one who created us loves us and will always love us; and that changes us. It gives us a kind of security that nothing else can. It gives us the freedom to take risks, even the risk of loving others.

All relationships carry with them obligations, and our relationship with God is no different. The whole theological history of the world, as given in the Bible, records God’s attempts to enter into covenant with humanity. God made a promise with Abraham to be the God of his descendants if they would be faithful [Gen 15]. God remembered that covenant when Israel was captive in Egypt [Ex 2:24], and countless other times. Unfortunately, God’s people forgot it as often as God remembered it – and finally we are told that God gave up on covenants written with words and chose instead a covenant that would be written on our hearts [Jeremiah 31:31-33].

We are part of that covenant. It is a binding agreement where God cares for us and we serve God, and it is written not on paper but, to use the language of Jeremiah, it is carved into our hearts. The essence of our understanding of the first part of the Godhead is that we are loved by God and that we are in partnership with God.

How then do we relate to God? As Christians, we claim an intimacy with a God who considers us family. We are not just servants of God or vassals of God, we are children of God [ John 1:12, I John 3:1-3]. In practice, that means that in worship and prayer we can relate to God as our parent – as our Mother or as our Father.

There are some who object to the concept of God as Mother since most of us are more accustomed to the language of “Father, Son, and Holy Spirit.” Sex, however, is a construct of biology. Creatures that do not reproduce sexually are neither male nor female. God is unique, and does not reproduce, and when we were created as male and female we were created in the image of God [Gen 1:27].

As humans we can never have a full understanding of the person of God, and it’s hard for us to relate to someone as a person without thinking of them having a gender. Consequently, we pray to God as Father or Mother in an attempt to find an image of God that is accessible and real to us; while still recognizing that our image is limited. An important spiritual exercise is finding a way in prayer and study to prayerful relate to God that is real, and I encourage you to find one that is comfortable yet still cognizant of the holiness of God.

People find considerably more to debate when discussing the nature of God. There is, for example, a relatively new movement called Open Theism that questions whether or not God is omniscient. On the issue of omnipotence, even those who claim to be biblical literalists cannot agree about how omnipotent God is. Imagine, even those who claim that every word of the Bible is literally true and absolutely authoritative cannot find sufficient evidence within the Bible to convince each other whether we have some free will or God has absolute control.

Personally, I find those debates about as useful as the discussions about how many angels can dance on the head of a pin. God knows more than we do and is more powerful than we are. How much more so is not something that affects our day-to-day lives in the least. What is important for our discussion is to recognize that, for Christians, God is real and relational. God wants to interact with us – not as a distant overlord – but as a loving parent. As with our earthly parents, that relationship has expectations; but those expectations are rooted in love and mercy [James 2:13; Romans 5:20].

The most visible testament of that mercy is Jesus Christ. Jesus is the second member of the Trinity – Holy God in human form. In the first few centuries, the most passionate debates in the early Church were over the nature of Christ, and so it is in fact fairly easy to define exactly what the traditional, orthodox understanding of the nature of Jesus is.

The first conflict was over whether or not Jesus was fully divine. Arius, a Christian leader in Alexandria taught that Jesus was above the angels but subordinate to God. There is some biblical support for this view, including the fact that there are things that God knows that Jesus does not [Mt 24:36] and that Jesus asks God to change things for him [Mk 14:36; Luke 22:42]. Yet the first Ecumenical Council, the Council of Nicea in 325 c.e., determined – with much wrangling – that Jesus was in fact fully divine.

We don’t have time to go through the process of that debate or the ones that followed it. The simple answer is that, from that time forward, orthodox Christians have recognized Jesus as equal to God. Jesus is, therefore, not subordinate to God. This includes the understanding that Jesus is not subordinate to God's authority. Within the context of the cross, this means that Jesus was not ordered there to die but rather chose to go to Golgotha as a full member of the Godhead.

Some people carried that too far, and denied the humanity of Jesus. Led by a man named Apollinarius, some early Christians taught that Jesus carried with him the divine mind which had been merely implanted in a human body. The second Ecumenical Council, the Council of Constantinople in 381 c.e. corrected that error. From that point on, orthodox Christians recognized that Jesus was fully divine and fully human.

The third heresy to arise was linked to the other two. A Christian leader named Nestorius taught that Jesus’ humanity was incompatible with his divinity; and that he must in fact have been two people wrapped into one. The Council of Ephesus in 431 c.e. emphatically denied that, declaring that Jesus was one person.

Unsurprisingly, the fourth heresy carried the orthodox decision of the third council to an extreme – and Eutyches taught that Christ’s divine nature and his human nature were identical. The Council of Chalcedon in 451 c.e. reigned in that approach declaring that Christ did in fact have 2 natures.

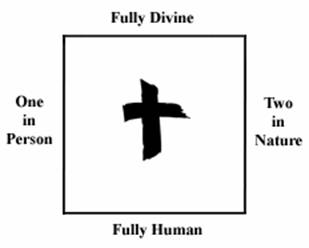

Combining the conclusions of these four councils gives us the boundaries for the orthodox understanding of who Jesus is. My friend Loyd Allen draws it as a box thusly:

These are the boundaries of the orthodox Christian understanding of who Jesus is. As with the Trinity, there are some inherent contradictions that seem illogical. Again, we follow a God who is beyond the limitations of the physical world and the boundaries of the scientific method.

Understanding Jesus in these terms is more than abstract theological wrangling. It means that as Christians we serve a God who – while transcending our understanding – has also stood exactly where we have stood. Jesus was tempted as we are tempted [Heb 2:18, Heb 4:15], he suffered as we have suffered [Heb 5:8], died as we will die [Heb 2:9], [Rom 5:21].

The efforts of the first four ecumenical councils are simply an attempt by the early Church leaders to keep some people from subtracting from the fullness of who Jesus is. Essentially, they said, “Don’t take away the divinity of the one who walked with us. Likewise, don’t take away the humanity and reality of our God.”

We serve a God who understands us. A God who befriended us [ John 15:13-15] and then taught us how to live as friends to each other. He also taught us how to be faithful without falling into legalism [MT 12:1-8]. Ultimately, the written Law fails us. More accurately, we inevitably fail the written Law. We either ignore it or we abuse it. And so God comes to us as Jesus, who showed us how to live the Law of God instead of just observing it. Within the context of our focus on transformation, Jesus’ life shows us visibly the ideal of what it means to be transformed as well as the ways in which a faithful follower of God transforms their world.

In Jesus we actually see what it is like to meet God. God touches us, even when no one else would dare to come near. In Jesus, God heals us, feeds us, walks with us, and teaches us. In Jesus God, dies for us. And in Jesus, God shows us the hope of resurrection.

Yet, after becoming Christians, we do not immediately ascend to Heaven to join Jesus. Until that day comes, we have the third part of the Trinity – the Holy Spirit. The Holy Spirit is the tangible presence of God in our lives right now.

There have been all sorts of debates about how the Holy Spirit is manifest in our lives. For instance, some denominations demand semi-miraculous signs of the Holy Spirit’s presence before recognizing a person’s salvation. Others build aspects into their worship service that – to me at least – have always seemed false. They claim that these elements are the movement of the Holy Spirit. Ultimately, it is not my place to judge the work of the Holy Spirit.

What all Christians can agree on, however, is that God works through the Holy Spirit to help us to understand the mysteries of our faith [ John 16:13]. It also comforts and guides us [ John 14:26], and can be relied upon when our own resources fail us [Mark 13:11].

In practical terms, being a Christian means believing that the work of God did not end with ascension of Jesus. As Christians, we believe that – through the Holy Spirit – God works within us to shape and perfect us according to God’s design [2 Cor 13:9]. Through the Holy Spirit we also become, as a group of believers, more than the sum of our parts. We become the very Body of Christ, united through the will of God and the work of the Spirit [I Cor 12:12-13].

This seems like a fairly simple idea, but I think that in practice Christians ignore the reality of the Holy Spirit more than any other aspect of the nature of God. Instinctively, we only respond to and act upon the things we can see and touch. We may give lip-service to trusting in the work of the Spirit, but I think in reality we trust much more in our own work.

In conclusion, the fundamental Christian understanding of God is that there is one and only one God who created us and wants to be in a relationship with us. God relates to us from above as a loving Mother or Father. God relates to us by our side as a fellow human in the person of Jesus. God works within us as the Holy Spirit. To close with the words of Paul, The grace of the Lord Jesus Christ, the love of God, and the Holy Spirit be with all of you [II Cor 13:13].

Bibliography

Erickson, Millard J. Christian Theology. Grand Rapids, MI: Baker, 1985.

Grenz, Stanley J. Theology for the Community of God. Nashville: Broadman and Holman, 1994.

Hinson, E. Glenn. The Church Triumphant: A History of Christianity up to 1300. Macon: Mercer University Press, 1995.

Julian of Norwich. Showings. Tran. Edmun Colledge and James Walsh. Mahwah, NJ: Paulist, 1978.

McFague, Sallie. Models of God: Theology for an Ecological, Nuclear Age. Philadelphia: Fortress Press, 1987.